FOLLOW THE WATER

Hidden cost of a B.C. town's water

Chapter 1

The buried price of too much manure

Chapter 2

The Fraser Valley conjures images of bounty. The green open farmland is brimming with succulent raspberries and blueberries, while dairy cow and chicken farms stretch one after another. An iconic rocky mountain range sits elegantly on the horizon.

The Valley is one of the most intensively farmed areas in Canada. The fertile land generates millions of dollars every year, contributing almost 40 per cent of British Columbia's agricultural revenue in 2015. Such prosperity comes at a cost. These days, it's clean drinking water.

In B.C., 28 per cent of the population relies on groundwater for domestic use. In the Fraser Valley, that number can vary from everyone living over an aquifer, the pools of groundwater used to draw drinking water, to 42 per cent.

Over the years, the region's small parcels of farmland have become swamped with mounting levels of manure from chickens, horses, hogs and even llamas, as well as synthetic fertilizers. The trouble with this manure is where it can go.

"We have more manure in the Fraser Valley than we have land to put it on - the entire Fraser Valley, and we don't ship the manure to Delta, and other places because it's too far, so that mean that we're over applying," said Ted van der Gulik, a former agriculture engineer for the province.

Chicken droppings or dung from dairy cows are often used as a fertilizer. Picturesque fields of raspberries will easily suck up the nutrients from the manure to help them grow. Others crops like blueberries, which are currently in the top five exports for B.C., don't absorb nitrate as well.

"It's very productive land. We want to keep the land in production, we want all that, but now we need to start managing water to that land, nutrients going onto that land, or nutrients going elsewhere, and all these sorts of things," said Van der Gulik as he taps the table in front of him to make his point. His serious gaze speaks of someone who knows how vital the Lower Fraser Valley is for B.C.'s food production.

With concentrated farming practices, where manure can be spread at high levels, comes greater risks to water quality. In B.C., the concentration of farming in the Lower Fraser Valley is estimated to be 14 times above the Canadian average.

"As you get more chickens or dairy in the Lower Fraser Valley or whatever, we have a limited amount of land that we could spread it on," said van der Gulik.

In 2016, there were over 2,500 farms spread across the six municipalities that make up the Fraser Valley. Moreover, nearly 40 per cent of farms in the Fraser Valley Regional District - an area which includes Abbotsford, Mission, Chilliwack, Hope, and Langley - are smaller than 10 acres. These small lands, combined with the intensive practices, create the increased risk of nitrate leaking into the environment and harming the groundwater people drink.

What is nitrate and why can it be a problem?

Nitrate is a colourless, odorless and naturally occurring element of nature. In the environment, nitrates are important to the growth cycle of plants. The average amount of nitrate in "pristine" water conditions are usually around 0.5 to 1.0 mg/L.

Too much nitrate, however, degrades water quality. Levels above 3 mg/L have generally been used as an indication of human activity in the area. Sources of this excess nitrate can be: high use of nitrogen fertilizers, animal manure and pesticides on sensitive areas, as well as poorly managed or constructed septic tank systems and water wells.

Too much nitrate is harmful to water. The Gulf of Mexico is renowned for its "dead zone," an area where the amount of nitrogen - the element from which nitrate is produced - is so high it smothers marine life. In January 2018, a group of experts from around the world met in New York City to discuss the current world crisis of nitrogen pollution. The group concluded that the world needs to halve the amount of nitrogen pollution put into the environment. If not, the world's water could see a rise in outbreaks of toxic drinking water incidents and dead oceans.

Over the years, urban sprawl in the Fraser Valley has rapidly expanded alongside these vibrant fields. Dense municipalities, such as Abbotsford and Chilliwack, now wrap themselves around the farmland.

Rising housing developments and influxes of people from burgeoning cities have fuelled new jobs, classrooms, art galleries and businesses. But they have also driven up the price of the land. A 2017 PostMedia investigation found the cost of farm land had risen from an average of $109,000 an acre in July 2016 to an average of $151,000 an acre by September, with rising farm prices in the Fraser Valley. To stay profitable, some farmers have begun to move their operations to the B.C. Interior or looked for ways to get more out of their existing land.

"Land is so expensive here, and you can sell your land here and set up a brand-new operation," said van der Gulik. "I know a lot of dairy that have moved to Kamloops and other parts of the province. "

"It's getting harder and harder to farm."

The effects of such concentrated farming go far beyond what can be seen on the land itself. Its impact seeps downwards into the groundwater. Once nitrate has drained into streams, rivers, or below the surfaces, it can begin to degrade water quality. It moves through and within the land's water like a hitchhiker, but one that stays along for the ride for years and years to come.

This has been a problem long in the making. Between 1960 and 1996 the number of cattle and chickens reared in the area increased by 150 per cent. From the late 90s to present day, the number of chickens on the land has gone up from 12 million to 18 million. As a result, the Fraser Valley hosts the highest number of farm animals per estate in Canada. All that animal waste needs to go somewhere.

"The amount of manure we produced in the Fraser Valley, if you go back 20 years and you put them into trucks, the trucks would line up from Vancouver to Regina,"said van der Gulik.

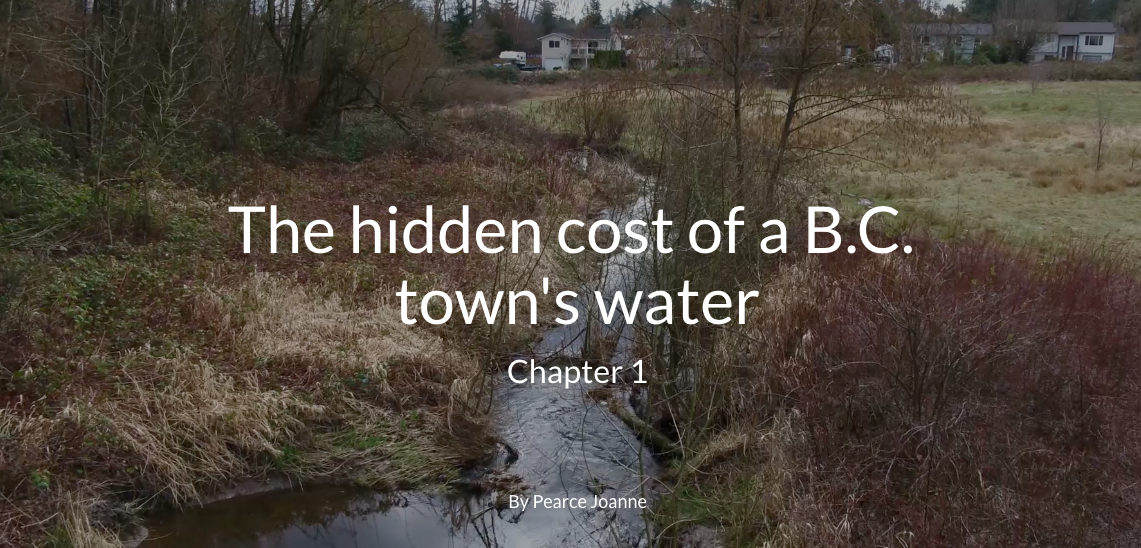

Schreier has spent his life studying water systems from around the world.

Schreier has spent his life studying water systems from around the world.

A dairy operation in B.C. will have, on average, about 135 milking cows.

A dairy operation in B.C. will have, on average, about 135 milking cows.

The present-day situation

From the air, the Fraser Valley is an unassuming patchwork quilt of fields. Small dots of livestock look like blots on the land, while streets carve out patterns alongside the farms. All the while the water beneath it, while not completely mapped yet, creates a patchwork of its own.

"For agriculture, the main problem is how to apply nutrients in a sustainable manner so that all nutrients are taken up by plants and no surplus is applied," said Hans Schreier, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia from the Faculty of Land and Food Systems.

Schreier has spent his life studying water systems around the world. One area where he has conducted some research has been within B.C.'s Lower Fraser Valley. During his lifetime, Schreier has seen the problem of excess nitrate in Lower Fraser Valley persist.

"The problem is that the number of livestock per farm have steadily increased, but the individual farm area has not changed much. This means more manure has to be applied to the same farm area, resulting in saturation," said Schreier. "Nobody wants to deal with it."

The increase in manure on small farmland has led to what Schreier calls "nitrogen saturated islands" across the Fraser Valley. These are areas where the soil is overburdened with nitrate. These islands are at high risk of leaking nitrate into the groundwater and contaminating it.

Trying to figure out accurate numbers for the muck that cows and chickens in the Lower Fraser Valley are responsible for leaving behind, and what is being done with the burgeoning amount over time, is challenging. The Agricultural Census released every five years provides the overall number of livestock farms, such as cattle, dairy cows, and poultry. The figures show the number of farms and the sizes of cow or chicken farms, but not necessarily what happens with the manure.

The lack of information makes trying understanding trends in the issue over time hard.

Every additional cow can have serious consequences for the groundwater. As the number of cows and chickens rises, so too does the risk of nitrates trickling into the groundwater.

Right now British Columbia lags behind other provinces and countries on strict policies that cap the number of animals kept on a small piece of land. In Ontario, nutrient management plans - a strategy created to help sustainably manage the nutrients on a farmland - are required for any cow or dairy farms which produce a certain amount of manure. That number will be calculated based on the size and type of animal.

Across the border, in Washington state, all dairy producers are required to have a nutrient management plan regardless of the number of cows on the field. Such plans are not a standard requirement for farming operations in British Columbia.

Nitrate is one of the most common contamination problems in groundwater and surface water around the world because it is so mobile. British Columbia faces similar challenges.

"Do we know we can manage nitrate better? Absolutely. Have we done it fairly better in B.C. in the priority areas? Probably not," said Oliver Brandes, the Co-Director of the POLIS Project on Ecological Governance based at the University of Victoria's Centre for Global Studies.

Better water governance, the rules and practices of protecting water use and quality, is seen as one part of what needs to happen in the Fraser Valley. Rivers, streams, and lakes are often also impacted by these levels of contamination.

"It's not like its surface waters are so well managed and groundwater isn't. I'd say they are equally poorly managed, so I don't think groundwater is alone it its problems," said Brandes.

"I think that because of the additional layer of understanding aquifer dynamics, and how the water flows underground, it does create an additional layer of uncertainty or challenge."

A further wrinkle in tackling the problem is that local governments are not the main decision-makers. There are few federal laws that directly address water, largely because it falls under provincial jurisdiction according to Canada's Constitution Act, 1867. The provincial government has primary authority over water management and protection. These responsibilities are divided among multiple ministries, each with their own set of regulations over the water. All of this makes for a complicated process of monitoring and enforcing water protection in B.C.

Land management practices, such as the storage, transportation, and application of manure as a fertilizer, are not regulated based on meeting drinking water quality standards in B.C. Reprimands are also largely not enforceable until after the pollution has occurred.

More than just about the water

Tackling water contamination is an issue that needs a coordinated approach, across all levels of government. The issues in the Fraser Valley, however, also illustrate how the problem is more than just about water - it's also about the food and land.

The pressure on the land is simply increasing. The Fraser Valley, sandwiched between towering mountains and long coastlines, is in one of the rapidly growing metropolitan areas in Canada. It is estimated an additional 1.1 million people will be living in the Lower Mainland by 2036.

Protecting agricultural land is one way the province has tried to sustainably manage the land. Between 1974 and 1976 the Agricultural Land Reserve was established, which priorities land use for farming. Despite this step, urban sprawl has continued to encroach on the land. The Kwantlen University's Institute for Sustainable Food Systems released a paper in March 2018 critiquing the lack of protection against the rapid loss of agricultural land.

The effect these changes have on groundwater is similar to a line of falling dominos. The increase of people in the area has led to significant increases in the price of land. The increased cost makes it hard for some farm businesses to be financially viable. To continue staying profitable, farmers needed to increase their productivity or move out of the area.

Underneath it all is the groundwater.

Certain municipalities, such as the Township of Langley, have made a point of trying to address their own groundwater challenges where they can. Over the years the Township has implemented a number of water management strategies and initiatives to better understand their water system. Not all communities, especially more remote and budget-limited towns, will be able to follow suit.

To move forward away from a historical misuse and lack of protection of groundwater, many feel a more harmonized and collaborative approach is necessary. "When I talk about governance issues and good regulation, you're looking at…the site, you're dealing with the region, you're dealing with province and national rules. Those collectively need to work together" said Brandes.

Change to the current regulations governing agricultural waste and groundwater are underway. To use groundwater for non-domestic purposes now requires a license, according to the Water Sustainability Act that came into force in February 2016. A series of recommendations on how to deal with manure on fields has also been submitted to the province in December 2017, with public comments received in January 2018.

It takes time to see results however, moving from a "Wild West" system of unregulated activity to one where groundwater is controlled and protected. It depends on what steps the province takes over the next four to five years.

"I'm optimistic because I think people are beginning to recognize not only the importance of water, but the connection that water has to whatever their doing, whether that's farming or, you know, local quality of life, community health, public health, all that," said Brandes.

"People are beginning to ask tougher questions like, ok well who's in charge? And who is responsible? And what can I expect? And I think that's all good because that reminds our political and government leaders that water isn't something you should just leave till it's gone bad because it gets very expensive to try and fix it at that point."

Tackling the legacy of water contamination

Chapter 3

Tanya Gallagher carefully reaches for the little white box sitting in the bookshelf behind her in her tiny office at the University of British Columbia. Tugging off the lid, she begins to neatly spread photos across her desk. The images she pulls out depict land above the aquifer that she has been studying for the past five years.

"The area I was looking at, the aquifer that I was looking at, provided groundwater to like 100,000 people and has this long-term issue of nitrate contamination," she said.

Gallagher is a 30-year-old PhD Forestry candidate at the Landscape Ecology Lab. Studying the Abbotsford-Sumas Aquifer means addressing a problem older than herself.

The Abbotsford-Sumas Aquifer is an underground pool of water that stretches 260-square kilometres across the U.S.-Canadian border and provides 100,000 Canadians and 10,000 U.S. farmers their drinking water. It is the most vulnerable aquifer in the province to pollution such as nitrate, a nutrient often found in fertilizers and farm animal manure. The aquifer has been tainted with it for the past four decades.

The issue is now coming to a head. For approximately 40 years, Abbotsford has relied mainly on the Norrish Creek and Cannell Lake for its drinking water. However, there is growing pressure to find new sources to sate the thirst of its residents as those water levels decline. One option under discussion is tapping once more into the Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer.

"In the past, the City of Abbotsford used that water for their drinking water, and then they had to abandon it because the nitrate values were too high," said Hans Schreier, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia who is a member on Gallagher's PhD supervisory committee.

"Now they're rethinking it because they've run out of water sources, and the other sources that are available are very expensive. The debate is, should we clean up the aquifer so that we can reuse the water, or should we look for another source?"

An estimated 25 per cent of the B.C. population relies on groundwater aquifers. That number is small when you consider how other provinces, such as Prince Edward Island, have 100 per cent of the population reliant. Ontario has the highest population, 1.3 million, dependent on groundwater.

Data on groundwater are currently being collected by a number of scientific studies and concerned farmers across Canada. Despite these efforts, scientists still don't know how much groundwater the country has, or how badly pollution from industrial activities such as mining and farming are affecting the country's groundwater. This is concerning because approximately one in four Canadians rely on groundwater for drinking water.

Nitrates, which can come from chicken manure and fertilizers, are applied to soil to help grow crops such as blueberries or raspberries. When too much is applied it can sink into the groundwater or run off into streams connected to aquifer systems.

Nitrate doesn't easily go away once it's in the water either. It takes decades for the liquid underground to once again become a pristine source of drinking water. It means that the problem is bigger than just one individual or generation.

"There's legacy effects of what you do on the landscape that then impacts groundwater," said Gallager. "Things that you put on the soil have the potential to leach down into the groundwater, and with so much agricultural activity in the area, you have both synthetic and organic fertilizers that get put onto the soil."

Gallager's own 2017 study, published in the academic journal Ecosphere in December 2017. found that the type and amount of crops, such as blueberries, raspberries, and pasture land, on the land explained some of the variability of nitrate concentrations found in the groundwater.

Decades of contamination

The earliest tracking of nitrate contamination in the aquifer can be traced back to the 1950s. By 1993, 54 per cent of the water wells studied over the Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer had concentrations of nitrate that exceeded maximum acceptable health standards. About 80 per cent of the aquifer was impacted by contamination, and the waste above the land was clearly visible.

"If you went back 20 years and you drove around above the Abbotsford aquifer, you would see piles and piles of poultry manure where the poultry farmers took it out of their poultry barn," said Ted van der Gulik, a former senior engineer in the Ministry of Agriculture and current president of the Partnership for Water Sustainability in B.C.

Rain would pour onto the piles and eventually drip down into the groundwater. Today that image of leaking manure piles is rarely, if ever, seen. It doesn't mean the effects on the aquifer are gone.

"Once it's been contaminated, it doesn't mean to say that we stop doing this and it's all good. It takes a long time, and the people in the States, at least on the Abbotsford aquifer, are concerned because that's where the water heads," said van der Gulik.

Over the past four decades, the amount of nitrate draining into the water has decreased in some of the worst areas - but it has also increased in others.

"We're still getting the nitrate spikes, and so that means that we're still doing things on the land that are not matching up with where we're going with protecting water quality and drinking water," said van der Gulik.

It's not all bad news.

In 1995, for example, The Sustainable Poultry Farming Group - an industry-led organization that helps coordinate environmental initiatives in the chicken industry - began shipping chicken manure from farms on the Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer to farms off the aquifer. It resulted in 100,000 cubic meters, the equivalent of over 130,000 cubic yards of manure being moved. It literally removed the problem. By moving the manure, the nutrients were no longer concentrated over the aquifer anymore.

Moving the manure can also help to repurpose it as fertilizer for other crops in the province.

"The dairy industry spreads their manure on their own land, or their neighbours land, and they do it in a manner that, for the most part is - ok you need a certain land base - but the chicken industry is more of a solid manure and you move it around to different places," said van der Gulik.

However, farmers can only remove the manure so far from the site before it becomes too expensive. With large numbers of chickens found over the aquifer, it means that there is still too much waste being produced. There is more manure then there is space to put it.

Tanya Gallagher is familiar with the challenges groundwater can present, having grown up in a Florida county that relied on septic tanks.

Tanya Gallagher is familiar with the challenges groundwater can present, having grown up in a Florida county that relied on septic tanks.

Storage of manure has also improved as more farmers cover or properly store their manure in a way that prevents the rain from seeping the manure into the groundwater. New policy recommendations that came out November 2017 suggest changes to the Agricultural Waste Control Regulation are being considered. This could mean that further steps to help reduce water contamination risks will be taken. Technologies have also advanced to the point where the manure can be traced to find out whether it came from a cow, chicken, or another source of pollution.

"We've moved a long way from where we've been 20 years ago. There's a lot of good things that have been implemented and changes that have really changed the picture," said Gulik.

But there's still more to do.

"It's the low hanging fruit. It's the easy ones to do," said Gulik. "We're now moving into things that aren't as easy, they're a little harder to do. Cost a little bit more money, cost a little bit more management time."

Research published in April 2017 has shown underground water pools are more vulnerable to present-day contamination and pollution than previously thought. Even if there was an immediate halt to the spread of fertilizers and manure, the drinking water would suffer from the contamination of 20 years ago.

The Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer has attracted more attention in recent years, in part due to an escalating dispute over B.C. manure flowing across the border and affecting U.S. farmers in Washington State.

"A large part of the aquifer drains very slowly into the U.S. Some of it goes north, but a lot of it goes south," explained Professor Hans Schreier.

The divided groundwater and different regulations and laws in each country make addressing that difficult.

There are international efforts under way too in the Nooksack watershed, a body of water that sits across Washington and British Columbia, to determine the nitrogen problem that exists there. Water from Abbotsford-Sumas Aquifer, as well as several streams from Canada, contribute contaminants to the Nooksack watershed. The study will provide a comprehensive nitrogen balance that will show the extent of the nitrate problem, and provide options on how to reduce the nitrate input into the system.

"We have a lot of international rules on stream waters, surface waters, but we virtually have no international rules on transboundary aquifers," said Schreier, who has been studying these challenges for decades.

People like Schreier, who began the first investigations into contaminated water, have started to pass the torch onto the next generation. For PhD student Tanya Gallagher, that means sharing the duty of protecting our water sources.

"It could take a long time, but I think that shouldn't stop us from wanting to take these best management steps, today, in order that we curb these nitrate values," said Gallagher. "Even if it takes us a decade to see the effects of it, I think it's important to do this today."

"It comes down to being good stewards of the land, and in that part, I just mean being able to apply your nutrients in a responsible way. In a sustainable way."

Drone footage by UAViation Aerial Solutions