Highliners in Vancouver: A Connected and Limitless Community

Locations for highlining keep growing thanks to imaginative and stoked community members.

Shaun Haney came to Canada from Australia with a goal. He wanted to establish a new highline within two years while in graduate school for geology. Less than six months after he arrived in Vancouver, he met and exceeded his dream, establishing two new highlines in one weekend.

If you don’t know what highlining is, the sport involves walking on a thin, one-inch wide piece of webbing, tensioned between two anchor points. Highliners wear a harness with a climbing rope attached to the webbing, so they swing below the line when they fall.

Shaun Haney on "Taken for Granite"

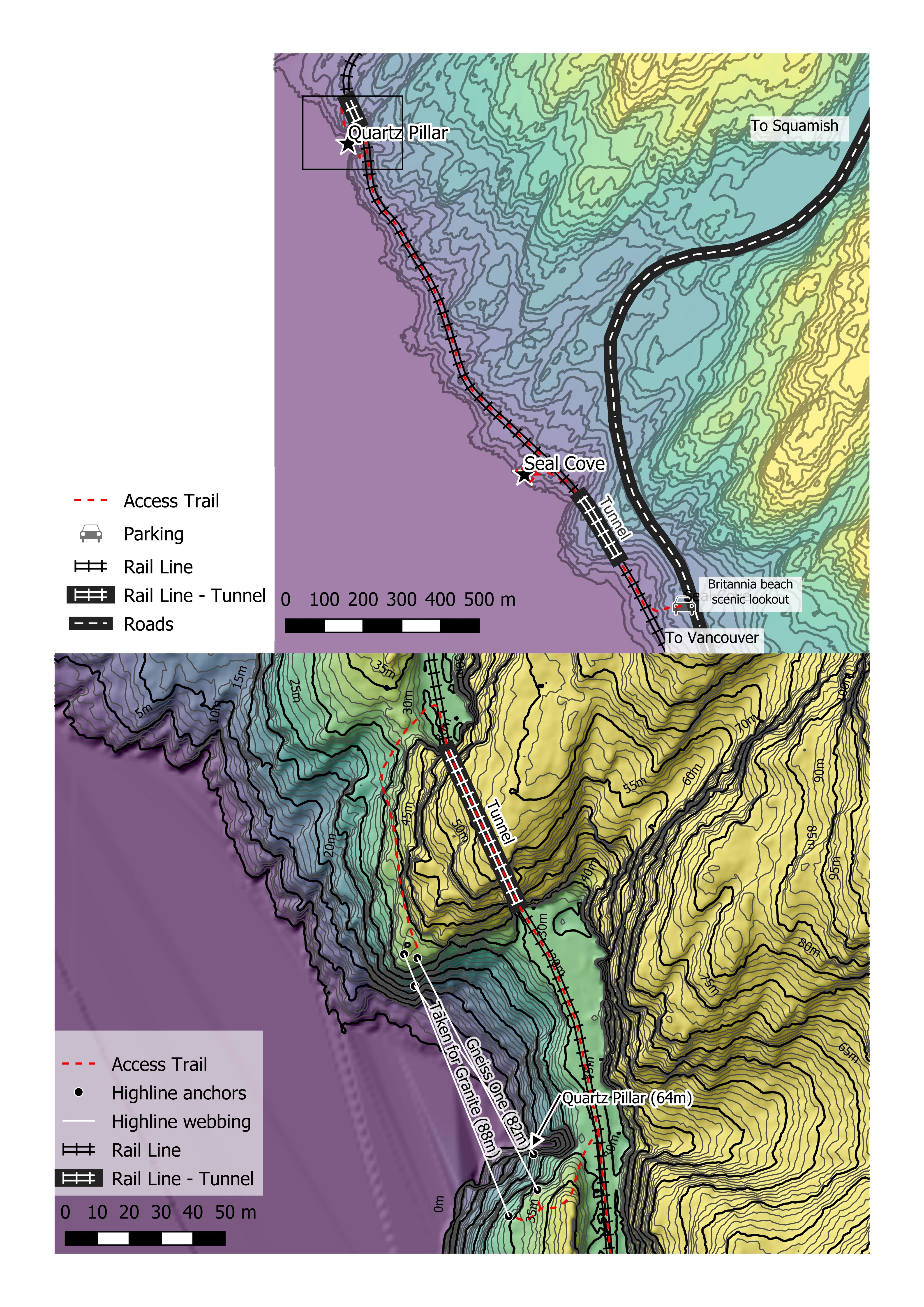

On a chilly Saturday morning, November 19, seven highliners (eight if we're counting me) met at the parking lot of Brittania Beach lookout, south of Squamish. Friends juggled and stretched before going over all the gear necessary to establish two new lines. By ten a.m., the crew started the hike down to the coast, seeking an area called Quartz Pillar.

From left to right: Matthieu Plante, Shaun Haney, Kevin Perocheau and Ryan Keogh assessing the area.

From left to right: Matthieu Plante, Shaun Haney, Kevin Perocheau and Ryan Keogh assessing the area.

From left to right: Matthieu Plant, Shaun Haney and Miriam Abel looking to the far side of Quartz Pillar.

From left to right: Matthieu Plant, Shaun Haney and Miriam Abel looking to the far side of Quartz Pillar.

Once at Quartz Pillar, the group looked at the location and divided work into the far and the main side. The main side is where tension is applied to a highline and highliners hangout. It’s usually chosen based on access to seating and ease of tensioning the highline. The far side is, you guessed it, the far side where highliners walk before turning around and heading back.

To establish a new highline in nature, you can use trees and/or bolts in rock. As Shaun wasn't experienced at bolting, he tapped Matthieu Plante.

Shaun chose Matthieu for his knowledge and personality.

"He's just such a loving and giving person who has the experience that you would need or want to do this sort of thing. And he's just always been keen with anything that's been suggested," said Shaun.

For Matthieu, establishing new lines is one of his favourite aspects of the sport.

"You go somewhere that no one has ever been and create. It could be done wrong; it can be done right. So it's nice to just make it the best you can, explore your options, and make things happen. It's very satisfying," said Matthieu.

To determine where to bolt, Matthieu used a hammer and listened to the sound of the rock. A high-pitched "ting ting" means the rock is strong and has no air pockets. A low “tonk tonk” sound means the rock has air pockets and isn’t suitable for bolts.

Drilling into solid rock takes effort. Matthieu and Shaun took turns boring into granite. Before they could bolt, Matthieu realized he forgot some equipment needed for bolting. Evan Willson headed back to Squamish to get the missing tools. Shortly after, one of their drills started to lose power. Matthieu called Evan, who went and picked up another drill. Rigging is a team effort, and the communities' problem-solving ability is part of the sport.

After drilling three holes for one line, the team drilled three more holes for a second line that would be established the next morning.

Matthieu Plante blows dust out of a newly drilled hole.

Evan Willson reaches down to a newly installed bolt.

As Shaun and Matthieu were bolting, Kevin Perocheau, Jason Stephens and Ryan Keogh brought a tagline over to the far side. A tagline is a long piece of cord. To get the tagline across, Kevin swam in the frigid water of Howe Sound.

The webbing was sent over from main side to far side by attaching it to the tagline and pulling it over. After being connected to both sides, the line was tensioned and ready for sessioning.

Shaun Haney and Ryan Keogh on "Taken for Granite."

Kevin Perocheau takes in the exposure.

In highlining culture, the first person to send a line gets to name it. Sending a line requires the highliner walk across it without falling.

Jason Stephens had the pleasure of sending the 88-meter line. While folks were tossing out potential names, there was a lot of support for "Taken for Granite." Jason liked the reaction, and so the line was officially named.

The name is also a wink to the area. The line is at a place called Quartz Pillar. But the rock type, geologist Shaun Haney explained, is granite.

The next day, a second line was established and named "Gneiss One." The 82-meter line was sent by Matthieu Plante, who didn't want to break up the rock-themed names.

The site had one line established 11 years ago. It's a 64-meter line called "Quartz Pillar."

Map curtesy of Shaun Haney

Map curtesy of Shaun Haney

While highlining is visually appealing, social, and physically demanding, it's also incredibly mental and emotional.

Jason Stephens explained the mental nature of the sport gracefully. One of his favourite stories to tell about his experience on the line is "the self-doubt story."

"While I'm walking, it's almost like there's a timer that goes off in my head and is like, 'Oh, you're due for a fall soon.' Like, I've been on for a certain amount of time, and it feels like that timer is running out," said Jason.

When he's doubting himself, he asks himself questions.

"I think to myself, 'How do you respond to these thoughts?' Right? Like, 'Do I want to analyze them? Do I want to go in on them? Do I want to continue thinking about the topic of self-doubt? Or do I want to replace them with self-love?' And so when a self-doubt thought would come up, I just say 'I love my doubt.' You know, like, I can just be friendly to myself."

This shift helps him stay on the line longer and continue progressing.

Evan Willson said he experiences a spectrum of emotions while highlining.

"Sometimes it is pure bliss and joy. And I can't even describe how happy I am. Other times it can be very frustrating, angry, tiring, exhausting. Overwhelming. But at the end of the day, I know it is always super happy and super fun and full of stoke. But sometimes I just get in my head and I put too many expectations on myself."

Both Evan and Jason have praise for the community and the work that goes into making the sport as safe as possible.

Evan said, "If you want to find yourself, and a community ... if you want to get out of your comfort zone ... then I'd say [try] highlining."

He went on to say that while highlining does seem "dangerous and super, super scary," the community is full of mentors willing to teach.

"Everyone's always stoked to have people learning how to do this safe. Because it's not just our lives, it's everyone else's lives when you're rigging."

As long as people ask questions, carry gear, bring stoke and food, they're welcomed into the community.

"It's always gonna be about the community. Because we're hanging out with everyone all day long. We're sharing laughs, sharing joy, sharing food. We tend to not hang out with other people, other than the highlining community. Just because it brings us all so much joy."

Jason said the community sets highlining apart from other sports.

"What's nice about the community is opposed to other athletic communities [is that] it's not competitive. You have to work as a team to rig. And then you also have to practice trust with your teammates, because often, you only rigged one anchor; you didn't see the other side. But you know the person that did rig that side is someone you truly trust, and you're literally trusting them with your life. That builds a connection. "

Evan Willson on "Gneiss One."

Evan Willson on "Gneiss One."

Karla Meza Ruiz gets ready to stand.

Karla Meza Ruiz gets ready to stand.

Miriam Abel sits on "Taken for Granite."

Miriam Abel sits on "Taken for Granite."

Ryan Keogh (left) and Mattieu Plante (right) play on the lines.

Ryan Keogh (left) and Mattieu Plante (right) play on the lines.

When asked how he felt about the project, Shaun said, "fantastic."

However, he went on to explain that "it doesn't feel like a personal achievement. My knee is not great. I'm not good enough to send these lines yet. But the support has been amazing from everyone who came and helped, and everyone who came to check out these new lines."

For Shaun, highlining is everything.

"The vast majority of my friends have come from this community ... I've spent the vast majority of my time exploring the outdoors with these people. They're just so full and giving with love and support and stoke."

While he's accomplished his goal, Shaun has more on the horizon. He hopes to establish, solo rig and send a line - all in one day.

A note from the author:

Thank you to everyone involved in this project for allowing me to document our community. It was a labour of love. Your skills, determination and talent are awe inspiring.

Liz McDonald