She Speaks in Power

[“Amalankhula ndi Mphanvu”]

The story of Mwayi Mphande, a Malawian hip-hop artist and singer-songwriter living in Vancouver, Canada.

By Katrianna Skulsky, University of British Columbia

Crossing Continents: A Rap Story

Mwayi Mphande sat in her studio apartment in East Hastings, Vancouver, stirring a cup of coffee in time with the discordant symphony of screeching tires and honking horns rising from the street below. It was April, 2025, and for over a year now, she had been navigating the strange terrain of her new identity as a “protected person”: a refugee or person in need of protection as determined by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

That morning, like countless others, she steeled herself for the quiet grind ahead. By seven o’clock that evening, she would have watered vegetables in a community garden, boarded a ferry bound for Bowen Island, worked an eight-hour shift at a licensed cannabis dispensary, and—if the night granted her enough breath—written and recorded a new song in a friend’s studio.

Mwayi Mphande standing just outside her home along East Hastings, Vancouver.

Mwayi Mphande standing just outside her home along East Hastings, Vancouver.

But just five years earlier, her days followed a very different rhythm—one shaped by the pulse of live audiences and the streets of Malawi, Africa, where she wandered with a notebook in hand and chased lyrics on the wind. Now, survival had taken center stage, and songwriting, once her lifeblood, had been pushed to the periphery.

Where "Lady Pace" took root

Mphande, twenty-eight, was born and raised in Malawi, Africa, the third of five children. Growing up, music was not just an art—it was the pulse of her very being. It awakened her in the stillness of the mornings, flowed through her food, and guided the cadence of her studies and work.

At thirteen, something clicked—an inner rhythm revealed itself, subtle but insistent. She found herself drawn to rhyme and tempo, her words beginning to dance on their own. It started like a spark, small and sudden, where she discovered, “I could write, I could sing, I could rap.”

As she began performing around her community, word of her talent traveled. One day, a local musician, moved by the raw passion for music, approached her with an offer to collaborate. Then came the stage.

“I was fifteen,” Mphande recalled, “and I was on the biggest stage of my life.” The event was the Lake of Stars Festival—one of the largest music gatherings in Malawi. What might have been a moment of overwhelming fear transformed, mid-step, into something else.

“It ended up being a really good experience,” she said, the memory flickering behind her eyes. “When I went up on stage, all my fears just melted away. There were so many people—maybe three hundred thousand.”

It was the beginning of something much larger than a performance. It was her first taste of what it meant to belong to music—and for music to belong to her.

As Mphande’s career began to take root, so too did the branches of connection that would carry her far beyond home. One day, in the midst of Malawi’s vibrant creative scene, she crossed paths with Patti DeSante—a visiting activist from Bowen Island, Canada, dedicated to supporting African-led platforms and artists in advancing women’s rights.

Though they came from opposite corners of the world, something clicked. A quiet understanding passed between them, the kind that doesn’t require explanation. They became fast friends, drawn together by a shared love of art and expression.

Moved by Mphande’s talent and spirit, DeSante extended a unique invitation: to leave Malawi, come to Canada, and nurture her music on new soil.

“At first, I wasn’t really into it—I love my home,” Mphande recalled when she was first invited to move to Canada. “But over time, looking at my circumstances and how hard life had become, I thought, ‘Yeah… let’s give it a go.’”

Mwayi performing on stage in Malawi, 2017.

Mwayi performing on stage in Malawi, 2017.

Ad for Mwayi's second performance at Lake of Stars, Malawi, 2018.

Ad for Mwayi's second performance at Lake of Stars, Malawi, 2018.

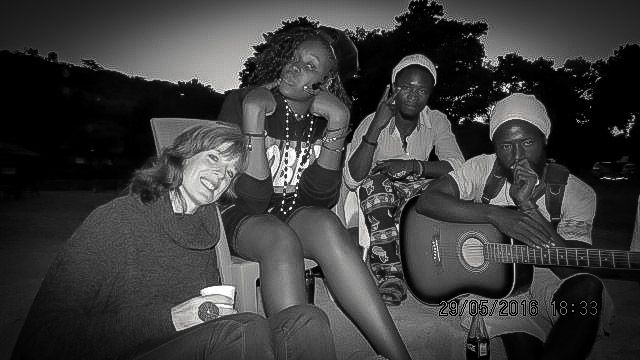

Patti DeSante (left) and Mwayi Mphande (second from the left) in Malawi, 2016.

Patti DeSante (left) and Mwayi Mphande (second from the left) in Malawi, 2016.

Oceans away, worlds apart

When Mphande was twenty-three years old, she stepped off the ferry and onto the damp wooden planks of Snug Cove, Bowen Island, British Columbia. “It’s rainy,” she spoke into the silence, announcing her arrival to a place that had never heard her name.

Back home in Malawi, Africa, she had been Lady Pace—a hip-hop artist and a bold voice that echoed through crowds of thousands. Her verses carried power, her name carried weight. Now, oceans away, she was simply Mwayi—the rain didn’t care for stages or accolades.

Snug Cove, Bowen Island, British Columbia.

Snug Cove, Bowen Island, British Columbia.

The first time I met Mphande was during the holidays of 2020, at a small dinner on Bowen Island, a place that, like the rest of the world, wore the pandemic's isolating grip. She sat curled in an armchair, quiet to the point of vanishing, as though letting the cushions carry her elsewhere. By day, Mphande babysat for a local family; by night, she soldered beats and verses in the dim solitude of a basement.

When I asked if she was enjoying her time here, I recall how she smiled, testing the words in her mouth: “Oh, yes.” It carried layers—the tone of someone who had absorbed Vancouver’s quiet epidemic: masking pain with politeness.

The pandemic had swept away the pillars of her musical growth—live performances, creative collaboration, and the simple act of being seen and heard. With no stage to stand on and no artistic community to anchor her, the dream she had carried across oceans—from the streets of Malawi to the shores of Bowen Island—began to drift with each passing day.

Starting fresh and studio sessions

Just as she was beginning to question her place in Canada, a chance meeting with Bowen resident Shael Wrinch altered the rhythm of her story. Wrinch, a music producer formerly known for his Beatty Lane recording studio in Vancouver, remembers meeting Mphande at a local event she was performing at on Bowen Island.

“When I first met Mwayi I thought she could rap but wow—her Chichewa lyrics, they were beautiful," recalled Wrinch.

Three days after arriving in Canada, Mphande was invited to perform at the Commodore Ballroom. “I was just told 'oh come on stage', and I didn't know what kind of a stage it was, but I did it, and that's when I met Shael,” she recalled. "Getting the right connection with music I feel like started with getting to know Shael.”

Mwayi Mphande recording music in Shael Wrinch's "Stone Hill Studio" on Bowen Island.

Mwayi Mphande recording music in Shael Wrinch's "Stone Hill Studio" on Bowen Island.

From that moment, the two became creatively inseparable.

Over the years, Wrinch and Mphande have forged a musical partnership, co-creating all three of her albums with sounds that mirror the island’s quiet cadence while staying subtly connected to Mphande’s musical roots in Malawi. Every week, without fail, they come together—to chase down new beats, revisit half-finished ideas, or simply lose themselves in improvised sessions.

Getting in sync with Shael Wrinch

“We just start tinkering, experimenting...and I don't think we plan on stopping, that's for sure,” Wrinch said.

He has become her producer, her collaborator, and, a trusted friend—breathing life back into the music she thought she’d lost.

“She's grown tremendously and she isn't afraid to try something that most people might be like 'that's not for me',” Wrinch told me. “Mwayi just goes 'okay, lets try it'.”

Becoming "Black Pace"

“Lady Pace” was a stage name accidentally bestowed on Mphande by a fellow musician back in Malawi, when her music first began to echo beyond small crowds. She never quite felt like a lady, not in the way the word implied—but she wore the name anyway, like an ill-fitting coat she wasn’t ready to shed.

That changed in 2021, when she was invited to shoot her first music video. It was then she considered redefining herself—not just in sound, but in name.

Mwayi Mphande (Black Pace), official music video for her song "Mutuvwa Cha", 2021.

Mwayi Mphande (Black Pace), official music video for her song "Mutuvwa Cha", 2021.

“I was like, I’m Black, and I’m still on my pace,” she said with a grin. “I look like this—I might as well own it.”

Since then, Mphande has brought her evolving sound to stages across Canada, performing at AfriCa Fest Victoria, the Vancouver Folk Festival, and in clubs tucked into the pulse of downtown Vancouver.

“There’s always a little bit of resistance,” she admitted. “But you’ve just got to put yourself out there and say, ‘Hey—I’m here, and I’m going to perform.’”

Her early music in Malawi was a vibrant fusion of hip-hop, Afro beats. But since arriving in Vancouver, her sound has shifted, broken open, grown stranger—and truer.

“It’s very experimental now, very weird,” she said, laughing. “But it’s also something I really love. And I think that’s what music should be—the freedom to find your own essence in it.”

Growing—with Rainbow Refugee

As Mphande began to expand her musical identity, she also found a growing sense of belonging through Rainbow Refugee—a Vancouver-based nonprofit that advocates for safe, equitable migration and builds communities of care for those fleeing persecution.

Her arrival came at a serendipitous time. Pat, the organization’s board leader, introduced her to the Robson Community Garden, where Rainbow Refugee tended three humble plots, growing everything from collard greens to onions and tomatoes.

Though she had little prior gardening experience, Mphande embraced the invitation. Each week, she made the journey from Bowen Island to join other members in the soil—digging, watering, laughing. It gave her something vital: a renewed pace of life.

“She came from Bowen Island every week—she didn’t have to—but that’s just who Mwayi is,” Pat recalled. Years later, Pat still speaks of her with admiration. Like the vegetables she carefully nurtured, Mphande’s sense of community began to root and bloom.

Pat tending to one of Rainbow Refugee's garden plots at Robson Community Garden in Vancouver, B.C.

Pat tending to one of Rainbow Refugee's garden plots at Robson Community Garden in Vancouver, B.C.

Soon after joining Rainbow Refugee, Mphande found herself grabbing drinks and swapping stories late into the night with members of the team; people who suddenly felt like a second family. She began performing at community events, including International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia and PRIDE 2023, reclaiming a stage that had once felt impossibly far away.

Mwayi Mphande visiting Robson Community Garden to water Rainbow Refugee's plants.

Mwayi Mphande visiting Robson Community Garden to water Rainbow Refugee's plants.

These days, when Mphande isn’t rushing to work or lost in song with Shael, she slips away to the garden whenever she can. It remains her sanctuary—a quiet thread of nature woven through the noise and velocity of Vancouver. Here, among the soil and leaves, she sings to the plants, clears her mind, and—for a moment—lets the world fall away.

“You just feel so full as a person,” she said. “You forget the things that were weighing you down. Shutting off the world is hard... but that was the easiest way to do it.”

Rainbow Refugee's garden plots, numbered 78 and 79, at Robson Community Garden in Vancouver.

Rainbow Refugee's garden plots, numbered 78 and 79, at Robson Community Garden in Vancouver.

In that stillness, lyrics often found their way to her.

“When I’m writing,” she added one day, kneeling beside Rainbow Refugee’s planter box and looking up with a soft smile, “that’s when all my therapy happens. Everything happens when I’m writing.”

Embracing her identity

Among the truths that have slowly surfaced through her music is one she has carried for much of her life: “The thing I’ve wrestled with is the fact that I’m queer, that I’m gay.” She paused, remembering the first time she heard—really heard—that this part of her wasn’t something to fear. “Rainbow Refugee taught me that being gay is actually okay,” she said. “But that’s really hard to reverse in your head.”

In Malawi, her home country, homosexuality is illegal—punishable by imprisonment. As Mphande began to embrace her identity and piece together a life in Vancouver, she applied for refugee status in Canada, a process she describes as deeply exposing.

“I had to give evidence that I’m gay,” she said. “And then they decide, on the spot, whether your case is okay or not. So as you can imagine—it feels like being tried.”

In August 2024, Mphande was granted protected person status in Canada—news she received with a strange blend of relief and sorrow.

“The reason you can’t stay in your country,” she said, her voice low and steady, “is because this is your identity. But then...you can’t go back. And everybody wants to be home. I want to be home. There’s always a difference between where you were born, where your family is, and where you end up.”

Moving on out, moving on up

One morning in mid-April, I met up with Mphande at her new apartment—a sunlit studio tucked along East Hastings, her first real home since arriving in Vancouver. The space reflected her spirit: bright, lived-in. Yet there were few traces of the life she’d left behind in Malawi. Guitars—three of them—rested against the walls like old friends, and a neat rainbow of sneakers traced the edge of the room, betraying her soft spot for style.

Mwayi Mphande sitting in her studio apartment in East Vancouver.

Mwayi Mphande sitting in her studio apartment in East Vancouver.

We sat across from each other, as we had countless times over the years. But this time was different. This time, I was in her space. Her home. And in her, I noticed something had shifted. She carried herself with quiet assurance—shoulders back, confident. She had finally arrived home.

Yet, she admits that living on her own isn't easy. “I have to do this and that and work, and put music aside because I have to make sure my bills are paid,” she admitted.

As we stepped out of the apartment, the noise and light of East Hastings greeted us—sirens in the distance, raised voices, the steady hum of a street that rarely rests. Across the street, two police officers loitered down the block, their discomfort palpable as they paused to question loose gatherings of people slouched against a cement corner. Mphande paced forward into the sunlight, undeterred, head raised to the sky.

“When you walk outside it sparks some emotions, you know sometimes it’s sad, sometimes it's heavy," she said looking outside her window. “But, sometimes when it’s really heavy out there, you get inspired, and you think of a line.”

Like her story, her songwriting endures—raw, unfiltered, and pulsing with power.